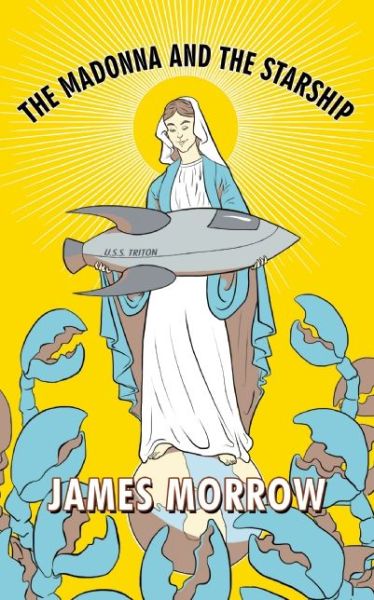

Check out James Morrow’s The Madonna and the Starship, hilarious send-up of the golden ages of television and pulp sci-fi, available in June from Tachyon!

It is New York City, 1953. Young pulp-fiction writer Kurt Jastrow’s world is thrown into disarray when two extraterrestrial lobster-like creatures arrive at the NBC studios. Though rabid fans of Kurt’s “scientific” alter-ego, loveable scientist Uncle Wonder, they also judge that the audience of a religious TV program is “a hive of irrationalist vermin.” To Jastrow’s horror, the crustaceans scheme to vaporize two million viewers when the next show goes on the air.

Now Jastrow and his co-conspirators have a mere forty hours to produce a script so explicitly rational and yet utterly absurd that it will somehow deter the aliens from their diabolical scheme…

1

Uncle Wonder Builds a Jet Engine

X minus ten seconds and counting! Nine, eight, seven! Step lively, cosmic cadets! Six, five, four! Time to scramble aboard the space schooner TRITON! Good job, cadets, you made it! Three, two, one… BLAST OFF with BROCK BARTON AND HIS ROCKET RANGERS! Brought to you by Kellogg’s Sugar Corn Pops, with the sweetenin’ already on it, and by Ovaltine, the hot chocolaty breakfast drink school teachers recommend! And now, stalwart star sailors, let’s race on up to the bridge, where Brock and his crew are about to receive an assignment that will hurtle them pell-mell into the dreaded “Coils of Terror,” chapter one of this week’s exciting adventure, THE COBRA KING OF GANYMEDE!

If I were a nine-year-old kid becalmed in the cultural doldrums of postwar America, nothing would have thrilled me more than the voice of Jerry Korngold announcing an impending episode of Brock Barton and His Rocket Rangers. Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoon, at four o’clock precisely, this indefatigable off-screen TV host delivered the program’s opening signature, bidding young viewers to enter a sacred and forbidden zone. Follow me to the throbbing heart of the cosmos, boys and girls. Come hither to infinity.

As fate would have it, however, in the early fifties I could not accept Jerry’s entrancing invitation, partly because I was no longer a child but mostly because I happened to be the head writer of Brock Barton and His Rocket Rangers. I liked my job. Just as our show enabled kids to fantasize that they were star sailors, so did my scripting duties allow me to imagine that I was a playwright, though I knew perfectly well that nobody was about to confuse a space schooner called the Triton with a streetcar named Desire.

While my primary Brock Barton obligation was to crank out a triad of weekly episodes, including a cliff-hanging climax for chapters one and two, I was further charged with writing and starring in a ten-minute epilogue to each installment, the popular Uncle Wonder’s Attic segment. Cut to me, Kurt Jastrow, a.k.a. Uncle Wonder, an endearing old tinkerer in a cardigan sweater. (I played the role behind an artificial grizzled beard and equally fake eyebrows.) Nestled in his attic workshop, Uncle Wonder has just finished watching the latest Brock Barton chapter with a neighborhood kid, freckle-faced Andy Tuckerman. The absentminded eccentric flips off his bulky Motorola TV and chats with Andy about the episode, and before long the boy pipes up with an astute question concerning some scientific aspect of the Brock Barton universe. (I tried to leaven the show’s bedrock implausibility with flashes of real physics and chemistry.) After rummaging around in the attic, Uncle Wonder finds the necessary materials, then proceeds to address the boy’s perplexity through a science experiment.

Under normal circumstances, the Monday, November 9, 1953, Brock Barton chapter called “Coils of Terror” would not have lodged in my memory. It was neither better nor worse than my usual attempt to write a script poised on the proper side of the rift that separates exhilarating junk from irredeemable dreck. As it happened, though, “Coils of Terror” occasioned my first interaction with the Qualimosans—I speak now of by-God extraterrestrials, complete with crustacean physiognomy, insectile eyes, and an antisocial agenda—and so I can easily discuss that episode without benefit of a kinescope or other tangible record of the broadcast. Don’t touch that dial.

Historians today call it the Golden Age of television, but for those of us who were actually there, it was nothing of the kind. Cardboard sets, primitive special effects, subsistence budgets: we were living in the Stone Age of the medium, and we knew it. True, my employer, NBC, did a classy job of informing viewers about current events—radio had taught them the art of gathering and broadcasting the news—and the network took a justifiable pride in its anthologies of dramas written expressly for the cathode-ray tube, but when it came to Brock Barton and other kiddie fare, the National Broadcasting Company was primarily concerned with holding down costs and sucking up advertising revenues.

That said, I was not complaining, at least not to anyone who exercised power at the network. Although the thought of spending my life writing juvenile space operas depressed me, I knew I had a good thing going, especially when I considered how far I’d come: all the way from Mom and Dad’s central Pennsylvania dairy farm to New York’s most celebrated bohemian enclave, Greenwich Village—an odyssey whose primary detour had found me in Allied-occupied Japan, working with my fellow U.S. Army conscripts to remind the deeply spiritual citizens of shrine-laden Kyoto that reconvening the Second World War would be a bad idea. When people asked me why I’d decided to seek my fortune in New York, I always replied, “I came for the trees,” an unconvincing answer—there are many more trees in central Pennsylvania than in the five boroughs—to which I immediately appended a clarification. “That is, I came for the greatest of all the good things trees give us, better than fruit or shade, better than birds. I speak of pulp.”

Such a savory word. Without pulp there was no Amazing Stories. Without pulp, no Weird Tales, no Planet Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories, Galaxy, or Astounding Science Fiction. Most especially there was no Andromeda, la crème du fantastique, a monthly compendium of Gedanken experiments clothed in the regalia of science fiction. During my adolescence I must have read over three hundred Andromeda stories, an educational experience for which I can thank my father’s bachelor brother.

Uncle Wyatt made his living teaching English at Central High in Philadelphia, and whenever Mom, Dad, and I visited his Germantown row house, I was allowed to descend into the basement and pore through his literary treasures, which included not only pulp fiction but also Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang, The Police Gazette, and the occasional girlie slick, illustrated with what we now call soft-core pornography. My uncle’s grotto smelled of coal dust, kerosene, and fungus, a fragrance that, owing to its association with his moldering periodicals, was the most exquisite I’d ever known. While the magazines devoted to ruthless pirates, fearless explorers, and daredevil pilots engaged my interest, it was the science-fiction pulps that truly mesmerized me, to the point where I decided that writing stories and novelettes for Andromeda must be the best possible way to earn a living. (This was before I understood that no human being had ever supported himself in this fashion.) At first my commitment to an extraterrestrial vocation was equivocal, but then one afternoon Uncle Wyatt joined me in his cave of wonders, set his palm on an Andromeda stack, and said, “The church of cosmic astonishment, Kurt. It’s the only religion you’ll ever need.”

“Church?” I said, fixing on the topmost cover, an exquisite image of a rocketship approaching a double-ringed planet, one loop paralleling the equator, the second passing through the north and south poles: dubious physics, but transcendent iconography. “Religion?”

“Indeed,” said my father’s brother, laying an affirming hand on my shoulder. Eventually, of course, I would transmogrify my memories of Wyatt Jastrow into a character called Uncle Wonder. “I only wish its scripture were better written.”

My course was now set, and in time my allegiance to the church of cosmic astonishment found me boarding the fabulous streamlined Crusader in Reading Terminal, detraining in Jersey City, and taking the ferry to New York Harbor—for how better to pursue my intended career than to pitch my tent within hailing distance of Saul Silver, renowned editor of Andromeda? I spent the next five weeks at the Gotham Grand, a fleabag hotel on the Lower East Side, surviving at first on $100 in cash from Uncle Wyatt, then scraping by on the wages and tips I received from waiting tables in Stuyvesant Town. Among my fellow Gotham Grand tenants were two other apprentice bohemians—Eliot Thornhill, a budding actor from Delaware, and Lenny Margolis, an aspiring “cultural journalist” from New Jersey—and one day the three of us decided that, if we pooled our resources, we could rent an apartment in Greenwich Village.

When I agreed to cast my lot with the thespian and the trend spotter, I didn’t realize the package would include the complete Encyclopaedia Britannica Lenny got for winning a national high-school essay contest. No sooner had we moved into 378 Bleecker Street, apartment 4R, than Lenny arranged for his parents to deliver all twenty-four volumes to our doorstep, a fount of knowledge from which he allowed me to drink promiscuously, especially after I taught him how to buy condoms at the corner barber shop. (Unlike most consumers of Uncle Wyatt’s girlie slicks, I read the advice columns.) Throughout my years of roughing it in the Village, Lenny’s Encyclopaedia Britannica became the college education Mom and Dad could never afford to give me.

Against all odds, Saul Silver bought the first story I submitted to Andromeda, “Brainpan Alley,” spun from the Britannica’s account of Sigmund Freud’s theories. A mad scientist, seeking to liberate his mind from the fetters of both moral convention and animal instinct, transplants his superego into a bronze statue of the fourth-century heretical monk Pelagius, even as he relocates his id to a stuffed orangutan in the American Museum of Natural History. As fate and plot contrivance would have it, the statue comes to life, likewise the taxidermal ape, and the two creatures spend the rest of the story alternately drubbing each other and making life miserable for the hapless genius who evicted them from his psyche.

“Dear Mr. Jastrow, you are an intellectual snob,” Saul Silver’s letter to me began. “However, the scene of the monk sucker-punching the orangutan was too delicious to pass up. Enclosed please find a check for $120. Sincerely, S. Silver. P.S. Send me more.”

That night I took my roommates out for sirloin steaks and beer at Chumley’s on Christopher Street. Eliot vowed to reciprocate the instant he got a part in a Broadway show, as did Lenny if and when an editor took a chance on his journalistic talents. Before the year was out, both promises were kept, for April found Eliot playing a palace guard in The King and I, and in June the Brooklynite paid Lenny $250 to write “The Celluloid Insurgents,” a feature about the phenomenon of “underground movies.” (He also got to keep the ancient Bell & Howell Filosound projector with which he’d studied the 16mm curiosities in question.) But neither the Rodgers & Hammerstein roast beef nor the guerilla-cinema brisket had tasted half so succulent as the protein that accrued to my Andromeda triumph.

Two more sales followed apace. “Knight Takes Bishop” told of Ivan Gerasimenko, chess master of the galaxy, who relinquishes his title when bested by an alien-built computer. On his deathbed Ivan learns that the uncanny machine’s program consists exclusively of his own preferred strategies and tactics, and so he passes away a happy man, realizing that he didn’t lose the final tournament, for the winner was his cybernetic self. (Everyone was reading Norbert Wiener that year.) “The Pleistocene Spies” was my first attempt at political satire, the target being the persecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, currently on trial for espionage, as they’d allegedly given away the secret of the atomic bomb to the Soviets. A primitive future society built on the ashes of a global nuclear war becomes locked in an arms race with an adjacent community. Two canny savages named Jurgus and Elthea are persecuted by the United River Tribes for allegedly passing the flint-spearhead formula to the Collectivized Mud Tribes. I thought my story quite clever, and so did Saul, but then the Rosenbergs went to the electric chair, an event that made orphans of their two sons, and suddenly “The Pleistocene Spies” didn’t seem remotely amusing.

I sold one more story to Saul that year, an androids-in-revolt allegory called “Rusted Justice,” and then the rejection letters started arriving, not only from Andromeda but also Astounding, Galaxy, Weird Tales, and even Planet Stories. It was obvious that the three-way intersection of Uncle Wyatt’s basement, my fevered cerebrum, and the Encyclopaedia Britannica would not reliably cover my share of the Bleecker Street rent. So I penned a science-fiction teleplay for children, outlined four follow-up episodes, and started pounding the midtown-Manhattan pavements, hoping that my Andromeda track record might land me an interview with some TV potentates.

I couldn’t get past the receptionist at the Dumont Network, and CBS proved equally impervious, but somehow I wrangled a thirty-minute audience at NBC with Walter Spalding, head of programming, and George Cates, the marketing director, who listened attentively as I described a series that would give ABC’s Planet Patrol a run for its money. (The executives were especially intrigued by my idea of concluding each episode with a geezer doing science experiments in his attic.) I left the meeting with a feather in my cap—not merely a feather, a billowing plume, and a credit to go with it: Kurt Jastrow, assistant writer and associate development chief for Brock Barton and His Rocket Rangers. Mr. Spalding would function as executive producer. Mr. Cates would corral a couple of sponsors. The universe was my oyster.

I was not long on the job before realizing that NBC’s new outer-space series had neither a head writer nor a development chief. When it came to penning the scripts and defining the program’s underlying sociological and political assumptions, Brock Barton would be a one-man band, Kurt Jastrow receiving $210 a week to play all the brass, woodwinds, and percussion, though my resourceful director, Floyd Cox, and my ingenious special-effects technician, Mike Zipser, could also claim credit for the show’s success. While the contract required me to run every teleplay past my bosses, they never suggested deletions or changes, as Mr. Spalding rarely bothered to read anything I wrote—the steady stream of fan letters convinced him to leave my bailiwick alone—and Mr. Cates read only far enough to verify that the hero would appear on camera for the umpteenth time eating a bowl of Sugar Corn Pops and, later, downing a glass of Ovaltine.

I quickly learned that the fraternity of television writers was divided into two camps. For the self-proclaimed “linguals,” live TV was the bastard child of that venerable art form called radio drama. According to this school, dialogue and narration were the sine qua non of the new medium, and it was always better to paint a scene with words, thereby engaging the viewer’s imagination, than to attempt an on-screen flying dragon, spouting volcano, or sinking ship, because whatever the technicians devised was bound to look ridiculous.

The rival faction, the “ocularists,” located the essence of television in the camera’s lens, not the mind’s eye. True, the medium did not allow for Hollywood-style opticals and stop-motion animation, but you could still employ models, miniatures, and painted backdrops. Indeed, the low-fidelity picture tube often made such images appear vaguely authentic. And, of course, thanks to the switching device in the control room, the director could take the various cathode-ray streams arriving from the studio floor, their contents having been dictated to the cameramen via headsets, and blend them into exotic composites. Through the switcher’s magic, an ordinary lizard could become a dinosaur—a simple matter of mixing camera one’s shot of a live iguana with camera two’s shot of a prospector cowering on a desert set—just as a sun-struck vampire could be turned into a skeleton, or a couple of actors in diving gear transported to the gates of an underwater city.

Ultimately I pledged my allegiance to the linguals. I was a published author, after all, a professional whose fiction had occasioned seven fan letters in Andromeda. And yet in writing my weekly quota of TV episodes, I always tried to give the ocularists their due—Floyd Cox and Mike Zipser favored this approach—and the adventure called “The Cobra King of Ganymede” was no exception.

The plot had the villainous ruler in question, the notorious Argon Drakka, threatening our solar system by breeding space-dwelling pythons of ever-increasing size, eventually creating a serpent who could gird a planet, Midgard-like, so that the inhabitants faced an unhappy choice between doing Drakka’s bidding and having their world crushed like a tennis ball in a vise. Monday’s chapter, “Coils of Terror,” found Galaxy Central ordering the space schooner to the moon of Jupiter called Ganymede, so Brock could investigate the rumor that Drakka was experimenting with extraterrestrial reptiles. Before embarking on the assignment, Brock collected his crew on the bridge of the Triton (an elaborate set that filled an entire quadrant of Studio One) including his fearless first lieutenant, Lance Rawlings; his prepossessing second lieutenant, Wendy Evans, a.k.a. the love interest; a slap-happy ensign, Ducky Malloy; a humanoid robot, Cotter Pin; and a talking gorilla, Sylvester Simian, whose intellect had been augmented through accelerated evolution. Shortly after the Triton landed on Ganymede, Drakka unleashed one of his creatures-in-progress, a serpent of intermediate immensity that dutifully sinuated across the sands toward the space schooner and wrapped itself around the hull. (I felt confident Mike Zipser could coax a live garter snake into embracing our Triton model.) Cut to a commercial: a non sequitur shot of Brock, now mysteriously relocated to Galaxy Central, enjoying a bowl of Kellogg’s Sugar Corn Pops. “And remember, kids, it’s got the sweetenin’ already on it!” Cut back to Ganymede. With a reverberant prerecorded hiss the snake constricted. The schooner buckled. Girders snapped. Rivets popped loose—and then, suddenly, the monster’s head breached the viewport, threatening to sink a huge pointy tooth into Wendy: a composite shot fusing camera one’s close-up of a snake-head puppet with camera two’s image of the Triton bridge. Fade-out. Cut to Brock doing an Ovaltine commercial. Dissolve to title card, FANGS OF DEATH.

Be sure to tune in Wednesday for ‘Fangs of Death,’ ” exhorted Jerry Korngold, “chapter two of ‘The Cobra King of Ganymede’!”

Up in the control room, Floyd ordered the usual dissolve to camera three: the familiar attic set, including a Motorola TV displaying, via a closed-circuit feed, the title card, fangs of death. (The rabbit ears were just for show.) After Uncle Wonder—yours truly, Kurt Jastrow—deactivated the picture tube, a fresh title card, UNCLE WONDER’S ATTIC, appeared over a close-up of the tinkerer’s acolyte, Andy Tuckerman.

Smiling benevolently, itching beneath my ersatz beard and eyebrows, I paced around amid the canonical collection of attic bric-a-brac—dressmaker’s dummy, steamer trunk, hurricane lantern, grandfather clock—and addressed Andy in reassuring tones. “Wendy sure has gotten herself in a peck of trouble, hasn’t she? But I’m not worried, Andy, are you?”

An exciting chapter, to be sure, though not free of the disasters to which live television was heir. Ducky Malloy had bobbled his first line, “Not Ganymede again, their bars serve the worst orange juice in the Milky Way,” which came out, “Not Ganymede again, their oranges serve the worst Milky Way bars in the galaxy.” (We’d be hearing from the Mars Candy Company about that one.) While coiling itself around the Triton, the snake had snapped off a stabilizer, betraying the space schooner as a mere balsa-wood prop. And when the reptile’s head penetrated the bridge, Lance Rawlings had glanced at the floor monitor, seen the composite, and started laughing uncontrollably, forcing Sylvester to provide his lines from memory.

“Brock will save the day!” declared Andy. I was not alone in my lack of affection for this unctuous child. Everyone at the network thought he was a pill. “He always comes through in the nick of time!”

“Right you are! Say, Andy, have you ever wondered what makes the Triton’s shuttle go zooming across the sky?”

“I’m guessin’ it uses a jet engine!”

“Yep!” Sidling toward my worktable, I pulled on a pair of canvas gloves. “And it happens we can build a jet engine right here”—I stared into camera three, its tally-light ablaze—“and so can all you kids at home.”

“Gee willikers!” exclaimed Andy.

“We start with an empty cylindrical ice-cream tub.” By now the camera-two operator had wheeled his rig into Uncle Wonder’s sector of the studio, so that, as I identified the engine’s components, Floyd could reveal each in close-up. “We also need an aluminum pie-plate, a basin of room-temperature water, two short drinking-straw segments, a lump of putty, a pair of kitchen tongs, and some chunks of dry ice.” Cut to camera three: a midshot of Uncle Wonder. I winked at the lens. “Kids, you can get your dry ice from the man who drives your Popsicle truck. Popsicle brings you Wild West Roundup every Tuesday and Thursday afternoons at four o’clock here on your local NBC station.”

“I see you’re wearin’ gloves,” said Andy.

“You bet I am. Never touch dry ice with your bare hands.”

I equipped the kid with his own gloves, and then we got to work. Under my supervision Andy punched two holes on opposite sides of the ice-cream tub, then inserted the straw segments, securing them with putty and curling them in opposite directions. I filled our cardboard jet engine a quarter of the way with warm water, rested it on the pie-plate, and set the plate afloat in the basin.

“Go ahead, Andy, fuel the engine.”

The kid seized the tongs and—plop, plop, plop—dropped three chunks of dry ice into the tub.

“Here’s how our machine works,” I said, fitting the lid back over the tub. “The heat of the engine-water causes the dry ice to dissolve quickly. The vapor escapes through the straw segments in two complementary streams of thrust. Our turbine reacts by—”

Right on cue, the floating tub-and-plate arrangement began rotating in the basin.

“Spinning!”

“Gollywhompers, that’s swell!” said Andy. “I think I’ll go home and make a jet engine of my own!” Whistling, he headed for the door. “Mind if I borrow these gloves? Safety first, right, Uncle Wonder?”

“Of course you can borrow ’em! Safety first!”

Dissolve to end title. Fade-out. Cut to NBC logo.

The operators of cameras two and three lost no time switching off their rigs and leaving the floor—they were scheduled to cover Sing-Along Circus in Studio Three—even as the audio engineer killed the boom mike and the lighting director doused the kliegs. Though free to go home, I elected to hang around the deserted attic set and practice Wednesday’s science experiment.

Because the next chapter of “Cobra King” involved Brock detonating a bomb inside a dormant volcano, I’d decided to demonstrate why bakeries and flour mills sometimes exploded. The setup included a small funnel resting inside an empty paint can with a perforated bottom. A rubber tube snaked beneath the can, one end bare, the other suckling the funnel’s spout. Before Andy’s popping eyes, I would fill the funnel with flour, place a burning candle in the paint can, seal it with a metal lid, and exhale into the tube, forcing the white powder into a fateful rendezvous with the candle flame.

The rehearsal went rather too well. No sooner did I perform the requisite puff than a detonation rocked the attic set, wrenching off the paint-can lid and hurling it into the hurricane lantern—smash, crash, tinkle, tinkle—even as a fireball blossomed atop the worktable. My first thought: if my trial explosion had intruded on the live broadcast spilling from Studio Three, the Sing-Along Circus people would never speak to me again. My second thought: thank God I’d decided to rehearse, since blowing up a child, even Andy Tuckerman, on live TV was the sort of disaster from which my career would never recover.

Cautiously I prepared my miniature mill for a second trial, adding fuel to the funnel—a mere teaspoon this time—then inserting the lighted candle. But before I could restore the lid to the paint can, Uncle Wonder’s Motorola flared to life, displaying an unstable but intelligible picture: perhaps a feed from an NBC camera, I thought, though more likely, considering the fuzziness of the image, a broadcast struggling to cope with the disconnected rabbit ears. The scanning-gun limned an outlandish life-form suggesting a svelte blue lobster with serrated claws and a grasshopper’s rear legs. Its visual system was tripartite—three large eyeballs protruded from its brow on pliant stalks—and its toothless mouth opened and closed along the vertical axis.

“Greetings, Earthling!” shouted the crustacean, a line I’d promised myself I would never use in a Brock Barton episode. “Salutations, O Kurt Jastrow! We have converted your television into a pangalactic transceiver! Even as you watch this broadcast, we are hurtling toward you from our home planet, Qualimosa in the Procyon system!”

“I see,” I said, suppressing a smirk. Evidently my counterparts at ABC’s Planet Patrol were playing a practical joke.

A second bipedal lobster entered the shot, as obese as its colleague was skinny. (Stay tuned for Laurel and Hardy in Two Chumps from Outer Space.) “We apologize for the murky image! When we talk again on Wednesday, our ship will be closer to Earth and the transmission much clearer!”

“Know this, O Kurt Jastrow!” cried the skinny lobster. “All the brightest people on Qualimosa adore Uncle Wonder’s Attic! In a galaxy riddled with self-delusion, your program stands as a beacon of scientific enlightenment!”

“I see,” I said, trying not to snicker. “I have trouble believing that, of all the programs emanating from Earth, you think mine’s the best.”

“Truth to tell, Qualimosa’s engineers are still calibrating our planet’s TV antennas!” the fat lobster explained. “Beyond Uncle Wonder’s Attic, we have thus far tuned in only Texaco Star Theater, hosted by a boisterous comedian who dresses in women’s clothes, and Howdy Doody, featuring a mentally defective child!”

“Well, if those are the choices,” I said, “then my show is indeed a beacon of enlightenment.”

“We humbly request that, during your Wednesday broadcast, you announce our imminent arrival!” the skinny lobster declared. “Please tell your viewers that, instead of a science experiment, Friday’s program will feature an awards ceremony!”

“Harken, O Kurt Jastrow!” the fat lobster demanded. “You will be the first recipient of a trophy forged expressly for those who champion reason in its eternal war with revelation! We mean to visit your attic set and, standing before millions of viewers on Earth and Qualimosa, present you with the Zorningorg Prize!”

“This is a gag, right?” I said. “You’re from ABC. Hardy har har.”

“A gag, O Kurt Jastrow?” wailed the skinny lobster. “Your hypothesis is false!”

“Hardy har har not!” added the fat lobster. “Behold!”

It really happened. I saw it with my own eyes. The dressmaker’s dummy, which normally sat inertly in the corner on a small tripodal stand, began to move. Clank, clank, clank went the three wrought-iron feet as they stomped across the attic set. Before I knew it, the headless automaton had marched past the steamer trunk, circled Uncle Wonder’s worktable, and returned to its original position.

“Praised be the gods of logic!” exclaimed the skinny lobster.

“All hail the avatars of doubt!” declared the fat lobster.

And then the Motorola went dark.

The Madonna and the Starship © James Morrow, 2014

“The absentminded eccentric flips off his bulky Motorola TV.” How did that get past the censors? But hey, it sounds like fun!

I read some of it outloud to my 14yr old son who is home sick today. He’s worried for my sanity; so I think this must be good.